I have deleted

my accounts

that were on

Twitter and Threads

and which

I clung to

despite

knowing better

Forgive me

they were unhealthy

so fashy

and so rage-baiting

warming, not burning

Let’s talk about stuff I liked in 2022. No, not the best of anything. Just stuff I liked. And not necessarily stuff that was released in 2022. Just stuff I found in 2022. OK? OK. Let’s go.

Marvel’s Midnight Suns: I know a lot of folks bounced off the story/dialogue/relationship stuff—and bounced hard. But a.) the core combat is so frickin’ magnificent that it’s really easy to forgive. The idea of tactical card combat with Marvel characters sounds ridiculous; it really shouldn’t work. But oh my, it really really does. And b.) I actually enjoyed the hell out of the story/dialogue/relationship stuff. The core conceit of “superheroes at home” is really compelling to me; I think any superhero fiction is at its best when it’s looking not just at the suits but the people in them. Yeah, it can get a little goofy at times, and the game is clunky in some other significant ways. But man, it just hooked me with both pincers.

Marvel Snap: I’m not sure if I dug Midnight Suns more because of Snap, or Snap more because of Midnight Suns, or neither? Or both? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ But this one really has its claws in me, too. The speed and simplicity are just perfect for quick little diversions, but there’s a real depth of strategy there once you get familiar with the game. This is probably unsurprising to fans of other CCGs; I never was one of those. But a single moment in Snap made me finally get the whole idea of deck synergy in a way that no previous game I’d tried was able to. (It was playing Odin after White Tiger at a location that had just morphed to Bar Sinister, if you’re curious. Just delightful.)

Vampire Survivors: I lived through the 16-bit era, so retro-styled games often make me roll my eyes so hard I can see myself think. But this one showed up one day on Game Pass so I decided to give it a try. And I was this close to quitting and deleting within the first five minutes. (“Where the hell is the attack button?!”) Many dozens of hours later I think it’s one of the most fiendishly addictive and subtly deep games I’ve ever played. Really cleverly done and oh no it’s on iOS now.

Into the Breach: I heard so much good stuff about this game that I bought it when it came out on Switch pretty much sight-unseen. And I…didn’t like it. It just did nothing for me. I bounced off. Fast forward to 2022 and Netflix’s push into games, which included an iPad version available free for subscribers, and I gave it another shot. And something about the touch interface made all the difference in the world. I lost track of how many times I beat it before eventually having to delete it for space reasons.

And of course I played Tunic and Elden Ring and Immortality and Atari 50 and they’re all great. Believe the hype. (And there are also a few notable games I haven’t played enough of yet to form an opinion, like A Plague Tale: Requiem and Pentiment.) But these four, man. These four got me.

Look, I do not watch a lot of TV. When I have downtime I tend to want to dive into a book instead of firing up even the most celebrated hot new series (a fact which will likely become very clear in the next section). But I did have some really great TV experiences last year. Like:

Midnight Mass: A dear friend of mine kept pushing me to watch this. He said he was convinced I’d love it, that it was practically made for me. I yeah-yeah-yeahed for months, because like I said, I just don’t really prioritize TV? And when some dumbshit website put a significant spoiler in a FRICKIN’ HEADLINE, I yeah-yeah-yeahed even harder. Then I ended up with a free weekend, when my wife and daughter were out of town, and decided to finally put it on and oh my sacred heart what an unbelievably great series. The writing, the performances, the cinematography—my god. Just unbelievable. I’d never seen any of Flanagan’s other stuff but now? I’ll watch anything the dude makes. I don’t think the show gave me nightmares per se but for weeks I’d wake up in the middle of the night and the first thing I’d think of was that scene. With Joe. You know the one. Oh, and the weekend that I ended up binging the whole series? It just occurred to me it was Easter weekend. I started the series on Good Friday. Might need to make it part of the yearly celebration now.

Continue reading “My Favorite Whatever of 2022”

Hi. So, as many of you probably know, I come from a very large family. With such a large group, there is a correspondingly large diversity of sociopolitical opinions, approaches, positions, beliefs—I dunno what you want to call it, I am SO TIRED. Long story short, it became pretty clear to me pretty quickly that a significant percentage of my loved ones might not be fully on board with the whole treating-COVID-as-a-real-and-serious-thing… thing. So in a fit of optimism and a need to feel like I was doing SOMEthing about *gestures wildly*, I sent the following e-mail to all 43 people on my sister’s family reunion mailing list. I tried to write it as simply, clearly, and non-confrontationally as I could, and I know it could be better but I feel like I got pretty close to where I wanted to get. That being the case, I thought I’d share it here in case someone else might find it useful. Feel free to crib from it if you feel driven to write a similar e-mail. And stay safe out there.

Hello family!

Sorry for piggy-backing on the [reunion] email but I have something I want to share with everyone, because you’re my family and I love you. It’s this:

Covid is extremely serious. But vaccines are extremely helpful. Please get your shots.

Look, I know there’s a lot of weird baggage around this issue. And before I go any further I want to clarify that the absurdly long message that follows is not, like, copy-pasted from somewhere else. This is all me — your brother, your brother-in-law, your cousin, your nephew, your uncle — and what I’ve learned by reading things by people whose job it is to know about this stuff. I am not one of those people! I don’t claim to know everything about these issues! (I will include sources so you can see where I’m getting my info from, though.) But among people who do actually know about this stuff, these things are very, very clear:

1. Covid is extremely serious. Early on in…all this…some folks tried to downplay the severity of the disease, saying it’s no worse than the flu (or worse, that it was a total hoax) and that the seriousness of the pandemic was being exaggerated for reasons I’m still not totally clear on. By now I hope we can all see that this approach was pretty misguided. As of this writing 4.7 million people have died of it.

I know none of us finds it easy to wrap our heads around numbers that big, so to add some context: That’s a bit more than the population of all of Northeast Ohio. Imagine literally everyone in your hometown just…gone — empty houses, shops, schools, for miles in every direction.

Of course, the flu is serious too! In the roughly 1.5 years since Covid hit, we could have averaged as many as 750,000 deaths from the flu. Still really bad! But Covid is six times worse. And that’s not taking into consideration “long Covid,” where some folks lucky enough to survive the initial onset of the disease continue to experience some of the symptoms for months afterward (and maybe even longer; it’s not fully understood yet). (Also, side note: I say “could have averaged” because this past flu season had dramatically fewer flu cases than average — like around one fiftieth —for reasons I’ll get to in a bit.)

So, yeah. Covid: It’s real bad! Which makes us really, really lucky that…

2. Vaccines are extremely effective. We currently have three Covid vaccines approved for use in the U.S.: Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson. The first two (those are the ones that require two doses) are currently shown to be at least 80 percent effective at preventing infection by Covid — even the more infectious “Delta variant” — and at least 85 percent effective at preventing getting sick from that infection. The single-dose J&J doesn’t seem quite as effective, but it still more than halves your chance of getting infected or getting sick. (All stats as of August 9, from here.)

(For more about effectiveness, here’s a good primer from the WHO, but basically “80 percent effective” means that the infection will only sneak through the vaccine’s defenses in about one out of every five people — when considering the group of all vaccinated people. So that apparent effectiveness can vary pretty significantly depending on specific situations; like, places where people are in closer contact might see more people getting sick because they’re more likely to be exposed to more people who are already sick.)

But the really great thing is that even if you get it after being vaccinated, you’re way less likely to get seriously ill from it than unvaccinated people. The effectiveness there gets into the high 90th percentile. (And the effectiveness against death from Covid is very close to 100 percent!) We hear about “breakthrough infections” a lot right now, and I personally know four vaccinated people who have tested positive. Of those four, though, one had no symptoms, two had what felt like bad colds, and one had to spend a day or two in bed. Compare that to a week of misery (at minimum) that Covid brings to unvaccinated people. If you ask me, that’s a pretty fair tradeoff, especially since…

3. Vaccines are extremely safe. I know this is a sticking point for some people. Here’s what we know: Aside from the kind of side effects you might get after a flu shot — slight fever, muscle aches, fatigue, etc. — there have been two issues that have shown any significant link to vaccines. First, a treatable blood-clotting issue called TTS showed up after some folks (mostly women) got the J&J vaccine, at the rate of no more than seven in a million. Three people who did not get the condition treated have died (page 26) — out of 8.73 million doses. The other thing is myocarditis that has shown up in a small number of (mostly minor-aged) recipients of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines. That’s a potentially bad issue if it lasts, but these cases seem to clear up quickly.

So why might we have heard stories about other illnesses or deaths from the vaccines? That’s probably because of how the CDC collects data. They have a database called the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, or VAERS, where anyone can submit details about conditions that arise after getting vaccinated. There’s two really important details in that previous sentence: 1. Anyone can contribute, and it’s not curated by the CDC. That is, it’s intended to be for collecting information, not for spreading information; the claims are evaluated and investigated, and when the scientists and statisticians see a legitimate connection, that then gets shared with the public. (That’s how we learned about TTS and myocarditis.) And 2. The system asks for any symptoms or events that happen after being vaccinated — but “after” doesn’t mean “caused by.” To use a kind of extreme example, if someone got hit by a car walking out of their vaccine appointment, this could technically be submitted to VAERS as a death following vaccination.

So there’s some statistics for you. I think it’s also useful, though, to consider a more personal side of vaccinations. Like, every living president (and their wives) have been vaccinated; every governor has been vaccinated; at least 80 percent of Congress has been vaccinated… These are people for whom death or debilitating illness would be a very big problem for a very large number of people. But they, their families, their staffs or administrations — they’ve all agreed it’s safe enough. (Source here.) I feel like that says something.

All that said, though…

4. Vaccines can’t do everything. This has been another source of contention, so let’s talk about what vaccines can’t do. So, we know that vaccines are very effective at preventing infection. What we don’t know at this point is whether it’s possible to carry and transmit covid virus without being technically infected. What we do know is that Covid is a sneaky little bugger that doesn’t like to let you know you have it for a few days. That’s one of the big reasons we’ve been in this pandemic for so long: You can have Covid for several days — and be infectious! — without showing a single symptom. And since no vaccine is perfect, that means that it’s entirely possible to be vaccinated, get a Covid infection, and spread it around to everyone closest to you without having a clue.

So how do we combat that? Well, first of all, it helps a lot if anyone who can be vaccinated, is vaccinated. Think of it like this (though I don’t think this math is perfect): If you have a 20-percent chance of getting infected while vaccinated, your vaccinated loved ones have a 20-percent-of-20-percent-chance of getting infected by you — that’s 4 percent. And their vaccinated loved ones who you don’t see have a 20-percent-of-20-percent-of-20-percent chance of getting infected by you. Thats less than one percent!

But because nothing is perfect, and we can have Covid without knowing it, it’s also really important to wear a mask and keep your distance when around unvaccinated people. I’ve seen a meme saying something like “If vaccines work, why do we have to wear masks? If masks work, why do we need vaccines?” The truth is, prevention methods complement each other. One virologist I follow calls it the “Swiss cheese method”: Each slice of Swiss cheese has holes, but if you layer a few slices from different blocks on top of each other, the holes are unlikely to line up. The vaccines are a slice of Swiss with very few, very small holes. Even something as “holey” as a bandanna can block a lot of them.

And if you worry that these methods don’t do anything, remember from like fifty-seven paragraphs ago when I mentioned the flu being practically nonexistent this past season? That’s because we were masking regularly, keeping our distance, and washing our hands. We have proof that taking these simple steps is effective!

To put it another way…

5. Your choices matter. We’re currently dealing with this more serious Delta variant of Covid because the virus has had time and opportunity to reproduce a lot, which means it’s had time and opportunity for mutations to appear that have made the current vaccines slightly less effective. A bad enough mutation could put us right back where we were early last year. The more chance the virus has to spread, the worse off we’re all likely to be.

But that means the flip side is true, too: Everything you do to make things harder for this virus helps everyone. Like, in the world. Getting vaccinated protects you, yes, but it protects your community too — and it also, even if just a tiny bit, helps protect literally everyone else on earth, by taking one potential host out of the pool, giving the virus one fewer opportunity to reproduce and potentially mutate. You’re especially helping those of us with kids who aren’t old enough to be vaccinated yet (and those with loved ones who are unable to be vaccinated for medical reasons).

I would be so grateful if you could help Eleanor in this way.

So that’s what I wanted to say. If you’ve read this far, I really appreciate it. I appreciate you taking my thoughts under consideration. If you find this helpful, please feel free to share it. If you have questions, I’d be happy to do my best to answer. (That’s why I’m sending this via BCC, so we don’t have a reply-all tsunami.) Please, whatever you do, stay safe. This pandemic will be over eventually. I’d really like to see you on the other side of it.

With love and optimism,

-joe

or, What to Expect When You’re Expecting to Never Feel Okay Again, Ever

I’m no stranger to loss. My dad died in 2003, my mom in 2006. One of my four brothers passed in 2012, another in 2013. And one of my dearest friends offed himself like an idiot in 2012.

But this past week has been hard.

Last Tuesday, after a freakishly quick sequence of unlikely health events, my nephew Dan died at the age of 33. There was no time to prepare, no feeling of reluctant relief at a cessation of suffering. He was fine…then he was sick…then he was gone. He left behind a wife of four years, who moved from South Africa to be with him, to join our vast family. (They met in World of Warcraft—a fairy-tale relationship in many senses of the term.)

Today was his funeral, and I couldn’t be there. (Work obligations, you know; when you’re self-employed you can’t always get bereavement time.) But I went to visitation yesterday, hugged his parents and three siblings as hard as I could, and told them that it will get easier. In time.

That’s a hard thing to believe in the moment. In the moment it feels like things can never get easier. And maybe, as my wife pointed out, maybe on some level you don’t want things to get easier. Maybe it feels like a small betrayal to let yourself heal. But like it or not, we heal. Things do get better. In time.

With that in mind, I wanted to share a few things I’ve learned about that process, from my experience going through it—as well as from being raised in the family business of funeral service.

1. However you grieve is the right way to grieve.

This may be the most important thing I’ve learned from my experiences with death. Everyone grieves in different ways; some may get angry, some may get goofy, some may make inappropriate jokes, some may go silent. It takes different forms even in the same person, over time—and no, it doesn’t always follow a handy five-step process. So grieve in the way that you grieve, and don’t give yourself grief over it! The important thing is to let it happen; the only “wrong way to grieve” is to not grieve at all. Don’t suppress it, and by all that is holy don’t be embarrassed by it! Allow yourself to feel what you feel.

And a corollary: Allow your loved ones to feel what they feel, too. There will be situations when your grieving process conflicts with someone else’s. Recognize that both are valid, and try to be respectful of each other: If it’s a problem for you, communicate that you don’t feel comfortable with that approach, and ideally you can find ways to do your own grieving out of each other’s way. But try not to judge. And try to forgive.

2. Take care of yourself.

In this country we have this odd relationship with death, where you’re supposed to be sad but not express your sadness too loudly. Where you’re supposed to put on a brave face but not experience any strain from doing so. Where you’re supposed to look out for every other person in the deceased’s life…except, sometimes, yourself.

Fuck that.

You’ve just suffered one of the most horrible, stressful experiences a person will ever have to experience. I hereby give you permission to be selfish for once. That can mean stepping out from the services whenever you feel like it; it can mean taking that vacation you had planned; it can mean unashamedly walking away if you don’t like what the person you’re talking to is saying about your loved one. You do you. It’s what your loved one would have wanted, isn’t it?

3. It will get easier.

I know it’s virtually impossible to picture right now, so I’m not going to spend a lot of time talking about it. But I just ask that you trust me: There will come a time—and no one knows when—that you discover that when you think of the person you’ve lost, the good memories have, improbably, started to outweigh the bad. Just a little. I wish I could tell you when that will happen.

4. But it might get harder first.

I hate to have to be the one to tell you, but I want you to be prepared. Right now, you’re probably in shock. And you’re definitely in an unusual life situation: You’re planning or participating in or have just participated in a funeral ceremony, which is weird and totally out of the norm. At some point, though, you have to try to go back to “normal” life. And that’s hard.

At first, you will feel that person’s absence always. You’ll feel it everywhere and in everything you do, like a missing tooth that you can’t stop touching. And that’s hard. You will carry this absence with you, like dark matter: invisible, defined only by negatives, and unbearably heavy. But in my experience, that’s not all that different from what you’ve already been doing.

No, in my experience, when things get hardest is when you’ve just started to heal. Your brain will have begun to block off the pain, and so eventually it’ll turn out that you don’t think about that person’s absence for minutes, even hours at a time.

And then you remember.

Please realize that grief doesn’t have an expiration date. You get to grieve however you want to grieve; you get to take care of yourself; you get to trust that it will get easier—for as long as it takes. Only you will know when you’ve healed enough to feel that you’re “done” grieving. Don’t let anyone tell you any different. And if you find yourself in this situation…

5. Ask for help.

By now you’ve probably lost track of the people who have told you “if there’s anything we can do…” That’s a great sentiment, but you’ve probably realized by now it’s not terribly helpful on the surface. People say that because they don’t know what specifically to offer to do, but if you’re like me you’re not about to just call someone up and say, “Hey, remember when you asked what you can do for me? Listen up.”

But what you need to realize is that people actually mean this. They genuinely want to help, they’re just not sure how. So try as hard as you can to put any awkwardness aside and take them up on it. Here are some phrases to get you started:

“Hey, so, it turns out I actually could use some help…”

“I didn’t think of it at the time, but would you be able to…?”

“Hey, I’m not quite on top of things yet, could you possibly do me a favor?”

I promise you that everyone who cares about you will be delighted to be able to help.

6. Get mushy.

Finally, I want to formally give you permission to be as expressive to your surviving loved ones as your heart can stand. If there’s one good thing about death, it’s that it reminds us that life is finite—but love is not. So hug your loved ones tight, tell them how much they mean to you. Cherish the opportunity to love and be loved. And know that, no matter what happens, that love will always be there.

Always.

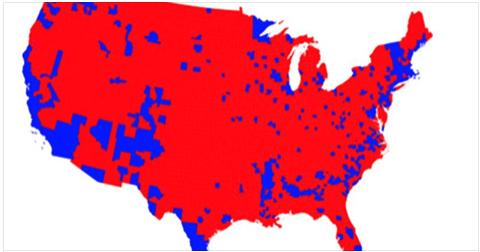

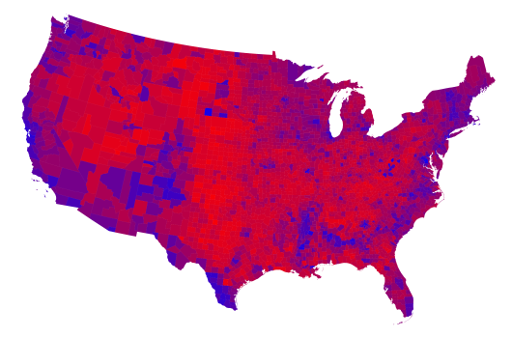

If you follow any conservatives on social media (and if you’re a liberal you really, really should) you may have come across one of the current talking points relating to the ongoing discussion about the Electoral College: maps. Such blazing red maps! Like this one:

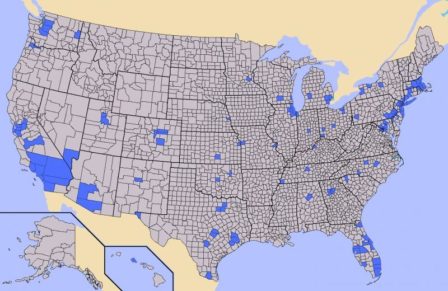

I saw that on Facebook, linking to an article called “What Elections Would Look Like WITHOUT Electoral College” [sic], from a site called The Federalist Papers Project. Oddly—one might even say suspiciously—that article doesn’t actually include that map, though it does include this one:

That’s a map of population density; the most populated counties are in blue. “Now, if the Electoral College did not exist, what would happen to the grey counties?” the author asks. “They would be forgotten, they would not matter. Only the most heavily populated areas would be courted for votes.”

The implication, of course, is that the Electoral College is in place to protect the gray/red counties (read: Real Americans) from the decisions made by those in the blue counties (read: Kale-Munching Freedom-Haters). And there’s really only one problem with this idea:

It’s complete, unadulterated, one-hundred-percent-free-range horseshit.

Of course, the reasons why it’s horseshit are many. First off, let’s deal with the subtext, especially the subtext of that incredibly misleading, Facebook-friendly teaser image. What the article is clearly implying is that the gray counties are actually red, which is to say conservative, while the blue counties are full of true-blue liberals. But unfortunately for the author, reality doesn’t quite agree. Here’s a map of how counties actually voted in 2016, per info available as of November 10:

(Longtime readers may recognize this as being similar to the one in my Purple Nation post from 2008, and it comes from the same source. I strongly encourage you to read that whole page if you want a sense of how the country actually votes.)

Looks an awful lot less red, doesn’t it? That’s because this map uses a gradient from blue to red rather than, say, marking a county that voted 50.001 percent Republican full red and a county that voted 50.001 percent Democrat as full blue. The result? Look at all that purple! And as I said eight years ago, purple is good:

It means we have people of differing political opinions living right next door to each other. When President-elect Obama takes office in January, he should have a mural of this exact map hung in the Oval Office—a constant reminder that he’s not working for one group or another, but for everyone.

(I’d suggest Mr. Trump do the same thing except I’m not certain he knows how to read maps.)

Second, let’s look at another of the Federalist author’s implications: that since there are more non-blue counties than there are blue ones, if the blue counties get their way it’s inherently unfair. The trouble with this idea is that elections aren’t decided by counties; they’re decided by people. And if there are more people in the blue counties than elsewhere, then them getting what they want is exactly fair.

In fact, this author’s defense of the Electoral College has the issue entirely backward. The Electoral College gives those gray-or-red counties an unfair advantage over the blue ones, and here’s why: Electoral College numbers are dictated by the number of senators and representatives assigned to a state. (Plus three for D.C.) A state’s number of representatives is determined by population, but—and this is the important bit—every state gets two senators no matter the population. Therefore, states with very low populations (which tend to be rural, which tend to vote conservative) get an edge in electoral votes in comparison to the population. This is why two of the last five elections have appointed Republican presidents in spite of many, many more people voting for the Democrat. (Secretary Clinton’s lead in the popular vote is up to about three times the population of Wyoming as of this writing.)

Population numbers and math can quantify this (see here). When we run the numbers we see that 35 states have a number of electoral votes that outweighs their population (36 if you count Tennessee’s razor’s edge). Twenty of those voted Republican in 2016, bringing in 121 electoral votes for Mr. Trump, or 132 counting Tennessee. The other 15 “outsized” states brought 90 electoral votes to Secretary Clinton.

In other words, to make a very long and mathy story short, it’s the less-populated parts of the country—those gray counties—that have the unfair edge, and if the Electoral College is supposed to prevent such things from happening it’s doing a very bad job.

Finally, let’s talk about the idea, bandied about often in conservative circles and alluded to in the Federalist article, that those blue counties don’t represent “real America.” (Because why else would it be a problem for a greater number of people to have a greater impact in the electoral process?) My response to this idea will be much more succinct, I promise you, because it can be summarized in three words:

Go fuck yourself.

Real America is the immigrant with the newly minted citizenship papers as much as it is the weathered plains-state farmer. Real America is the gristly New York punk rocker as much as it is the Mississippi preacher. Real America is the newly married urban lesbians just as much as it is the suburban soccer mom. Real America is the Clinton voter just as much as it is the Trump voter, because there’s no such thing as “real” America—”real” America is America, with all its glories and failures, and you don’t get to decide who is and isn’t a “real” American.

You don’t get to decide. What you do get to do is vote, like we all do. The problem is, this year more than one in a hundred of those votes, 1.5 million and counting out of about 135 million, were ignored thanks to the Electoral College.

One hopes that the red-map-waving Electoral College defenders would feel just as strongly about this issue if they ever found themselves on the other end of this equation. But I wouldn’t count on it.